Rockhound

by Loretta Velle | The things we collect.

We consulted the Magic 8 Ball. “Is Retta pretty?” you asked, then shook the toy, lightly, with your eyes closed. You didn’t fight the answer when it appeared, but read aloud in a small voice: “It is decidedly so.”

I keep a coupon in my desk drawer. I’m saving it. You wrote it out for me on scrap paper for my birthday, two years ago. You were nine, and I was a brand-new twenty-three. “Free hug.”

I keep candy wrappers, too, and cardboard boxes for mailing gifts. Beer and soda bottle caps Dad taught us to spot in parking lots—smashed under tires into tiny flat disks, the logo markings worn down to nothing, like rusty coins from an ancient time. At an estate sale, I pick up a hefty stack of scrapbook paper, still in its plastic wrap, never used. Three sheets of 3D froggy stickers, the adhesive long since dried out, but we could use tape. A sewing kit with five needles, five spools of thread, and a tiny pair of scissors. A book on rockhounding.

You had a wild toad you caught and kept as a pet. Not for long. You liked to pick the toad up and place it on your shoulder, let it creep along the back of your neck and settle on the opposite side. The toad seemed to like it there, in the warm curved space between your shoulder and your ear.

“I wish we didn’t have to teach children so much self-consciousness,” said the woman in her seventies, an artist. I found her art gallery on the way to my new life, on the drive from Texas to Oregon. Someday, I want to take you to see her paintings that are not paintings at all, but intricate works of embroidery. She weaves blue birds and sailboats and full moons, craters and all, with layers of delicate thread. In my dreams, we get to meet her together, and she tells you that you are lucky to be young, unaware of “all the fear-based stuff we’re taught in life.”

You put the toad on my shoulder once, and I didn’t flinch, just let it crawl closer to my neck even though its light steps tickled, even though I was scared we’d lose the toad to the tangles of my hair.

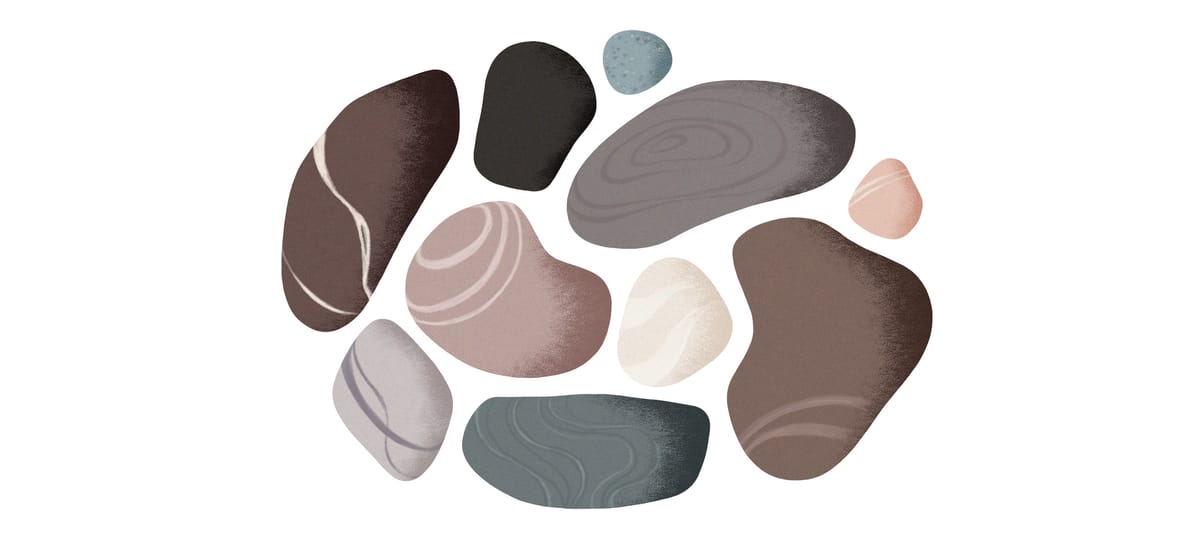

The sun comes out, and I step into the canoe. The moon is up, too; the trees are bare, the branches jagged and swooping like gentle pitchforks stabbing the blue sky. The boat is always moving. The water is never still. I wash up on a pebble beach and set out to hound for you.

Memories come and go, and I consult the internet. An article tells me what we did wrong, which was everything. We didn’t have the right materials for a good life. The toad needed a fifteen-gallon tank and three to four inches of substrate material to “absorb its waste and give it something to burrow into.” All we had were our hands and the slopes of our bodies, the warmth of our skin, and it didn’t occur to us that this might not be enough.

Marv from the rock shop agrees to identify my findings from the beach. He picks through my collection of special stolen stones, mumbling. He calls only a few by name: the yellow one is agate, the orange is carnelian, the green is jasper. “The rest I would have left by the river,” he says, in the end.

I ask Marv if he is sure the brown one isn’t petrified wood—the streaks, the knots, so resembling those of a tree—but he says, again, that it isn’t. “How can you tell?” I ask. “Just,” he shrugs, “forty years of looking at rocks.”

The trick with Magic 8 Balls, of course, is that you can only shake once. Otherwise, why ask your question at all?

Before I leave the rock shop, I buy you an Orthoceras fossil from the sale section. Marv smiles, and I notice his bottom teeth are crooked, teetering into each other, cradling each other to keep from collapse. He smells like smoke.

The toad needed to be touched “as little as possible,” according to the article, but you held it all day, trying to feed it dead flies and tiny pieces of strawberry. The article tells me the toad needed calcium supplement powder; it needed one or two live insects per day. Why didn’t we know this? Why didn’t we think to learn this, then?

I have a favorite song at the moment that you would have liked, before you could talk, before you could understand the words, before meaning came from anything but melody. It goes, “in the end, we found a way to complicate what really should have been a simple thing.”

After a few days, the toad was gone, and I asked you where it went. You said you’d set it free, that it had lost too much weight and its skin had turned gray and wrinkly, and Mom said you’d better let it go. She never liked it when you had pets in the house, anyway.

I might hold on to your coupon forever, just in case.

Marv says the fossil could be two to four hundred million years old. I can’t decide whether I should tell you this—on one hand, it’s mind blowing, and it might make my gift seem cooler. On the other hand, it’s practically unfathomable. You might learn this fact, mull the thought over in your mind, turn the fossil over in your palm. Then, you might shove the fossil in the far corner of a drawer and never look at it again.

Loretta Velle is a writer from the southern tip of Texas. She lives in Corvallis, Oregon, where she recently earned her MFA in creative writing at Oregon State University. She now works at OSU as a writing instructor. Listen to her read her short stories on Mystic Yarn and the Telescope Podcast, available wherever you find your podcasts.

This essay is a Short Reads original.

💛 THANK YOU to the 9 people who recently became supporting subscribers!

Want more like this? Subscribe to Short Reads and get one fresh flash essay—for free—in your inbox every Wednesday.